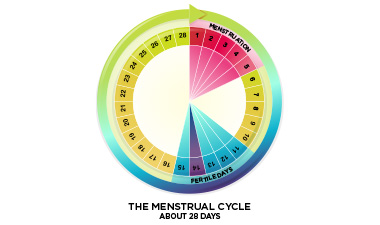

Understanding how menstruation works can help you understand how your own cycle works.

Your menstrual cycle is part of your body’s way of preparing for a possible pregnancy each month. Understanding how the process works is important, since you can use this information to help to either get pregnant or avoid getting pregnant, to better manage any menstrual symptoms you are experiencing, and understand when there might be a problem.

What is menstruation?

Menstruation is the technical term for getting your period. About once a month, females who have gone through puberty will experience menstrual bleeding. This happens because the lining of the uterus has prepared itself for a possible pregnancy by becoming thicker and richer in blood vessels. If pregnancy does not occur, this thickened lining is shed, accompanied by bleeding. Bleeding usually lasts for 3-8 days. For most women, menstruation happens in a fairly regular, predictable pattern. The length of time from the first day of one period to the first day of the next period normally ranges from 21-35 days.

Menstruation is the technical term for getting your period. About once a month, females who have gone through puberty will experience menstrual bleeding. This happens because the lining of the uterus has prepared itself for a possible pregnancy by becoming thicker and richer in blood vessels. If pregnancy does not occur, this thickened lining is shed, accompanied by bleeding. Bleeding usually lasts for 3-8 days. For most women, menstruation happens in a fairly regular, predictable pattern. The length of time from the first day of one period to the first day of the next period normally ranges from 21-35 days.

How does the menstrual cycle work?

The menstrual cycle is controlled by a complex orchestra of hormones, produced by two structures in the brain, the pituitary gland and the hypothalamus along with the ovaries.

If you just want a quick, general overview of the menstrual cycle, read this description.

For a more detailed review of the physical and hormonal changes that happen over the menstrual cycle, click here.

General overview of the menstrual cycle:

The menstrual cycle includes several phases. The exact timing of the phases of the cycle is a little bit different for every woman and can change over time.

| Cycle days (approximate) | Events of the menstrual cycle |

| Days 1-5 |

The first day of menstrual bleeding is considered Day 1 of the cycle. Your period can last anywhere from 3 to 8 days, but 5 days is average. Bleeding is usually heaviest on the first 2 days. |

| Days 6-14 |

Once the bleeding stops, the uterine lining (also called the endometrium) begins to prepare for the possibility of a pregnancy. The uterine lining becomes thicker and enriched in blood and nutrients. |

| Day 14-25 |

Somewhere around day 14, an egg is released from one of the ovaries and begins its journey down the fallopian tubes to the uterus. If sperm are present in the fallopian tube at this time, fertilization can occur. In this case the fertilized egg will travel to the uterus and attempt to implant in the uterine wall. |

| Days 25-28 |

If the egg was not fertilized or implantation does not occur, hormonal changes signal the uterus to prepare to shed its lining, and the egg breaks down and is shed along with lining. The cycle begins again on Day 1 menstrual bleeding. |

Comprehensive explanation of the menstrual cycle:

The menstrual cycle has three phases:

1. Follicular Phase (Days 1-14)

This phase of the menstrual cycle occurs from approximately day 1-14. Day 1 is the first day of bright red bleeding, and the end of this phase is marked by ovulation. While menstrual bleeding does happen in the early part of this phase, the ovaries are simultaneously preparing to ovulate again. The pituitary gland (located at the base of the brain) releases a hormone called FSH – follicle stimulating hormone. This hormone causes several ‘follicles’ to rise on the surface of the ovary. These fluid filled “bumps” each contain an egg. Eventually, one of these follicle becomes dominant and within it develops a single mature egg; the other follicles shrink back. If more than one follicle reaches maturity, this can lead to twins or more. The maturing follicle produces the hormone estrogen, which increases over the follicular phase and peaks in the day or two prior to ovulation. The lining of the uterus (endometrium) becomes thicker and more enriched with blood in the second part of this phase (after menstruation is over), in response to increasing levels of estrogen. High levels of estrogen stimulate the production of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which in turn stimulates the pituitary gland to secrete luteinizing hormone (LH). On about day 12, surges in LH and FSH cause the egg to be released from the follicle. The surge in LH also causes a brief surge in testosterone, which increases sex drive, right at the most fertile time of the cycle.

2. Ovulatory Phase (Day 14)

The release of the mature egg happens on about day 14 as a result of a surge in LH and FSH over the previous day. After release, the egg enters the fallopian tube where fertilization may take place, if sperm are present. If the egg is not fertilized, it disintegrates after about 24 hours. Once the egg is released, the follicle seals over and this is called the corpus luteum.

3. Luteal Phase (Days 14-28)

After the release of the egg, levels of FSH and LH decrease. The corpus luteum produces progesterone. If fertilization has occurred, the corpus luteum continues to produce progesterone which prevents the endometrial lining from being shed. If fertilization has not occurred, the corpus luteum disintegrates, which causes progesterone levels to drop and signals the endometrial lining to begin shedding.

What is normal bleeding?

There is a range of normal bleeding – some women have short, light periods and others have longer, heavy periods. Your period may also change over time.

Normal menstrual bleeding has the following features:

- Your period lasts for 3-8 days

- Your period comes again every 21-35 days (measured from the first day of one period to the first day of the next)

- The total blood loss over the course of the period is around 2-3 tablespoons but secretions of other fluids can make it seem more

How can I figure out what is happening in my cycle? When am I ovulating?

Simply tracking your cycle on a calendar, along with some details of your bleeding and symptoms can help you understand your cycle. Record when your period starts and ends, what the flow was like, and describe any pain or other symptoms (bloating, breast pain etc.), changes in mood or behaviour that you experienced. Over several cycles you will be able to see patterns in your cycle, or identify irregularities that are occurring. Use your own calendar or try this ‘menstrual diary’. There are also numerous apps available to help you track your period. If your periods come regularly every 21-35 days, chances are excellent that you are ovulating.

Beyond simple calendar tracking, there are a few ways to figure out the timing of your own personal menstrual cycle. Separately or used together, these can be used to help determine when and whether you are ovulating. Three methods you can try are cervical mucus testing, basal body temperature monitoring, and ovulation prediction kits.

Beyond simple calendar tracking, there are a few ways to figure out the timing of your own personal menstrual cycle. Separately or used together, these can be used to help determine when and whether you are ovulating. Three methods you can try are cervical mucus testing, basal body temperature monitoring, and ovulation prediction kits.

Cervical mucus testing

What is cervical mucus?

The cells lining your cervical canal secrete mucus. The consistency of this mucus changes over your cycle. When you are fertile, the mucus changes to a consistency and structure that permits the sperm’s travel on its way to your egg. When you are most fertile it will be clear, abundant, and stretchy. To give you an idea of the consistency, this type of fertile mucus is sometimes abbreviated as EWCM – egg-white cervical mucus. When you are not fertile, the mucus is sticky, cloudy, and doesn’t stretch.

How do I test my cervical mucus?

Watching the changes in the amount and consistency of your cervical mucus can help you understand your cycle. Here’s how it works: check your secretions before and after urinating by wiping with toilet paper. Alternatively you can insert a clean finger into your vagina to obtain a sample of mucus. Observe (and record) the consistency of the mucus, and use this chart to identify where you are in your cycle. Your mucus can be cloudy, white, yellowish, or clear. It can have either a sticky or stretchy consistency. Use your thumb and forefinger to see if the mucus stretches.

| Cycle timing (approx) | Consistency of mucus | Fertility |

| Day 5 | No noticeable mucus | Not fertile |

| Day 5-8 | No noticeable mucus | Not fertile |

| Day 8-12 | Minimal, cloudy, sticky secretions | Not fertile |

| Day 13-15 | Abundant, clear, wet, stretchy “egg-white” mucus | Fertile window – Before and during ovulation |

| Day 16-28 | No noticeable mucus | Not fertile |

You are most fertile on the days when you have abundant, stretchy mucus. This is not a foolproof method to prevent pregnancy.

Basal Body Temperature

What does ‘basal body temperature’ mean?

Your basal body temperature is your lowest body temperature when you are at rest. It is typically measured after several hours of sleep. As soon as you are up and about, your temperature increases slightly.

How does the basal body temperature method of fertility tracking work?

This method takes a few months of daily tracking to establish the specific patterns happening in your body. Your body temperature changes slightly in response to hormonal changes related to ovulation. Before you ovulate, your body temperature is usually between 36.2°C and 36.5°C. The day after you ovulate, your temperature will increase by at least 0.5°C (36.7°C to 37.1°C for example) and stay at this temperature until menstruation. To use this method, measure and record your body temperature as soon as you wake up, after at least 6 hours of sleep/rest. This means taking your temperature before you get out of bed and before eating or drinking anything. Take your temperature at about the same time every day. If you like to sleep in on the weekend you might have to set an alarm!

You will need a special “basal body temperature” thermometer, available at drug stores. Some thermometers have a memory feature that records the previous reading so you don’t have to record it immediately. You will see the half-degree increase in temperature the day after you ovulate. This method will help you determine if you are ovulating, how regular your cycle is, and how long your cycle is.

If your temperature doesn’t change over the course of your cycle, and your periods are irregular, it is possible that you may not be ovulating. You may want to get in touch with your health care provider.

Ovulation Prediction Kits

Ovulation prediction kits measure the concentration of the Luteinizing Hormone (LH) in your urine. This hormone is always present in small amounts in your urine but increases in the 24-48 hours before ovulation occurs. More advanced kits also measure estradiol, a form of estrogen that peaks on the day of ovulation. Instructions vary from kit to kit, so read the product insert carefully before using it.